IN THE HOUSE

The latest happenings at Hospitality House - August 2020 Issue

Farewell to Ronnie -The House He Always Knew…

By Joe Wilson

Last week, a friend of ours died on the street, where he lived. Ronnie Goodman, age 60, poet, father, ex-con, marathon runner, above all else, an artist – who lived life hard, every day. Ronnie Goodman found a creative home at our Community Arts Program, created a body of work that spanned several decades, mentored and supported by his long-time friend, Art Hazelwood. For those of us who knew Ronnie, he was complex, unpredictable, talented, troubled. He was a drug user. He was a gifted artist. He was a revolutionary poet. He was a marathon runner.

In Summer 2014, Ronnie trained for the San Francisco marathon and turned it into a fundraiser. Consistent with Ronnie’s penchant for the unpredictable, he donated the entire proceeds from the Run with Ronnie benefit – several thousand dollars – to Hospitality House. Ronnie Goodman. Artist. Homeless Person. Philanthropist.

Unquestionably, Ronnie chose his own path. For so many years, community advocates, counselors, social workers, and health professionals all tried to get Ronnie to come in from the cold, to let others help him. Ronnie chose not to follow where others tried to lead him. Having survived the cold, hard walls of San Quentin, Ronnie decided he would not go back inside.

He’d done that.

Those who knew him best also knew that the tragic stabbing death of his son, Ronnie Goodman, Jr., also a talented artist and muralist, left a hole in Ronnie Sr.’s heart that perhaps could not be healed. True to form, Ronnie Goodman created his own space for his art, on the street where he lived, and where he died.

In Summer 2014, Ronnie trained for the San Francisco marathon and turned it into a fundraiser. Consistent with Ronnie’s penchant for the unpredictable, he donated the entire proceeds from the Run with Ronnie benefit – several thousand dollars – to Hospitality House. Ronnie Goodman. Artist. Homeless Person. Philanthropist.

Unquestionably, Ronnie chose his own path. For so many years, community advocates, counselors, social workers, and health professionals all tried to get Ronnie to come in from the cold, to let others help him. Ronnie chose not to follow where others tried to lead him. Having survived the cold, hard walls of San Quentin, Ronnie decided he would not go back inside.

He’d done that.

Those who knew him best also knew that the tragic stabbing death of his son, Ronnie Goodman, Jr., also a talented artist and muralist, left a hole in Ronnie Sr.’s heart that perhaps could not be healed. True to form, Ronnie Goodman created his own space for his art, on the street where he lived, and where he died.

Former Hospitality House Executive Director Jackie Jenks had this to say about Ronnie Goodman:

“I keep going back to the Run with Ronnie event and talking with him about running the marathon. How free he felt when he was running. How he said that very act put him on a different plane in the eyes of others. He was just a runner - not a homeless person. Just someone running. I will never forget him saying that. And he would run for hours back then. After being incarcerated and battling so many demons, all the drugs...he said was most free when he was training for the marathon.”

“Free from the ugliness, and feeling so good about where he was and his ability to do something bigger than himself, to give back to a place and people who were there for him. That's what his art did and does every day. His impact on the world was always bigger than he ever knew…”

“I hope he knows now.”

First and foremost, all of us at Hospitality House extend our deepest condolences to Ronnie's family, his friends, and his incredible community of artists and creative souls, all indelibly touched by his artistic gifts, and his humanity. We thank you for sharing Ronnie Goodman with us. Though the loss of an artist creates a particular kind of grief - so does the loss of a friend and father.

We hope that Ronnie never doubted for a moment, that wherever his journey took him, the 'House would always be his home.

Rest in Power, Ronnie...

Click here to donate to the Ronnie Lamont Goodman Memorial Fund.

“I keep going back to the Run with Ronnie event and talking with him about running the marathon. How free he felt when he was running. How he said that very act put him on a different plane in the eyes of others. He was just a runner - not a homeless person. Just someone running. I will never forget him saying that. And he would run for hours back then. After being incarcerated and battling so many demons, all the drugs...he said was most free when he was training for the marathon.”

“Free from the ugliness, and feeling so good about where he was and his ability to do something bigger than himself, to give back to a place and people who were there for him. That's what his art did and does every day. His impact on the world was always bigger than he ever knew…”

“I hope he knows now.”

First and foremost, all of us at Hospitality House extend our deepest condolences to Ronnie's family, his friends, and his incredible community of artists and creative souls, all indelibly touched by his artistic gifts, and his humanity. We thank you for sharing Ronnie Goodman with us. Though the loss of an artist creates a particular kind of grief - so does the loss of a friend and father.

We hope that Ronnie never doubted for a moment, that wherever his journey took him, the 'House would always be his home.

Rest in Power, Ronnie...

Click here to donate to the Ronnie Lamont Goodman Memorial Fund.

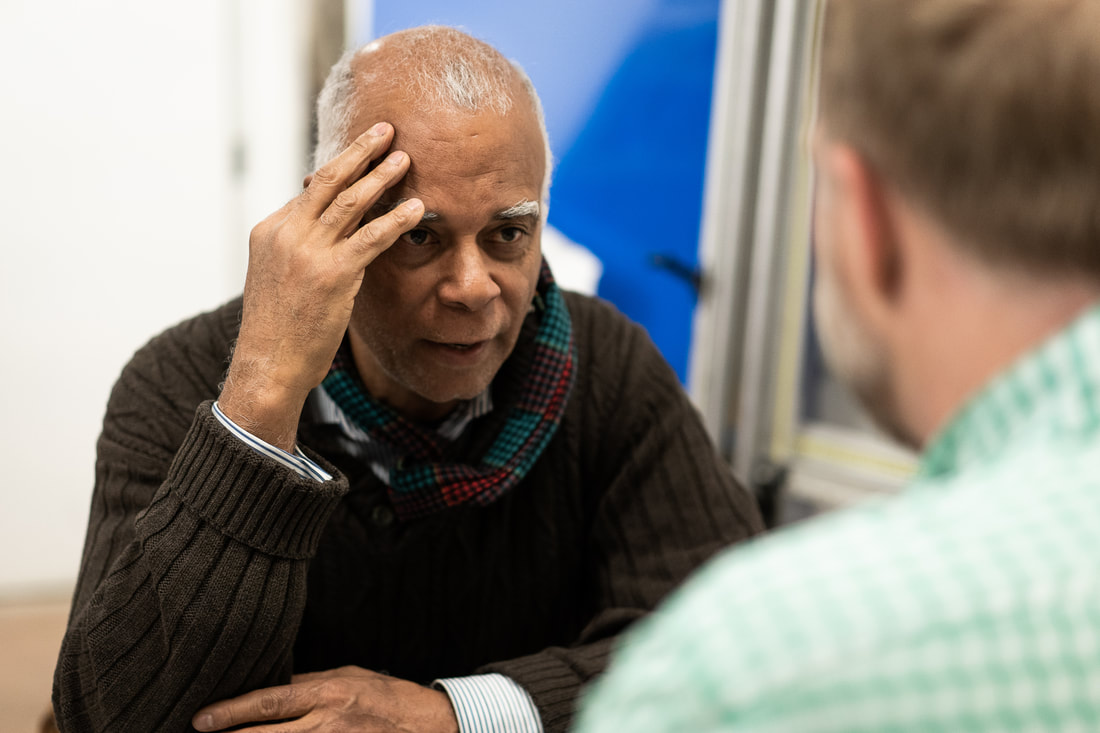

Dewayne Cobb: A Decade of Renewal

By Tess Davis

June 29, 2020 marked the ten year anniversary at Hospitality House for Dewayne Cobb, Program Manager of our Tenderloin Self-Help Center (TSHC). Hospitality House would be a very different place without Dewayne’s presence. It is with great joy and honor that we congratulate Dewayne on his ten years of service and commitment, and express our gratitude for his steady leadership, his constant example, and his unassuming grace. Dewayne embodies much of the founding spirit of Hospitality House and for this reason, I asked him to do an interview with me. Despite his initial reluctance to be the subject of any article about him, I’m pleased to tell you, he actually agreed. You have no idea how historic this is!

Dewayne began his journey at Hospitality House as both an on-call peer staff and on-call custodian, but it wasn’t long before he transitioned to a full-time position. Dewayne’s colleagues and supervisors quickly saw that he had a knack for connecting with his co-workers and community members alike. Dewayne possesses innate leadership qualities — a shoulder to lean on, an ear to bend, a great sense of humor to lift your spirit, and most importantly, a grounded presence to make you feel sane when the world seems like it’s getting ready to swallow you whole. There are not a lot of people that can do that. For Dewayne it came naturally. And still does.

Over the past ten years, Dewayne has worked his way up through several positions at Hospitality House, giving him useful insight on agency needs and issues. Dewayne’s extensive knowledge of the services Hospitality House offers, coupled with his engaging personality, make him an exceptional Program Manager at one of Hospitality House’s flagship programs, the Tenderloin Self-Help Center. Beyond that effective combination, Dewayne has a unique perspective on what genuine community support should look like.

Dewayne’s path to Hospitality House was a challenging one. After his release from prison, he resided at 111 Taylor, a so-called “community reentry center” located just blocks away from Hospitality House. This particular halfway house is owned by Geo Group, one of the largest private prison companies in the world. Geo Group operates “126 secure facilities, processing centers, and community reentry centers encompassing approximately 94,000 beds” in the United States. Put another way, that’s 126 prisons, immigration detention facilities, and halfway houses - profit-making off the misery of others.

Ironically, 111 Taylor is the site of the historic 1966 Compton Cafeteria Uprising, a collective queer resistence to police harassment and the first known LGBTQ related uprising in the United States (preceding the well known 1969 Stonewall Uprising in NYC). The founding of Hospitality House can be attributed to this uprising but we’ll save that story for another time.

Dewayne describes 111 Taylor as simply a bed to sleep in and nothing more. There was no support, no guidance, no direction.

“[111 Taylor] never connected me to jobs or resources. I had been incarcerated for a while, I needed clothing. I had never lived in the Bay Area. They sent me to job search, but I had nowhere to go, I couldn’t even get a bus token. They said ‘figure it out and bring us proof you’ve been job searching.’ I was lost here,” he admitted. “I don’t expect that much from most people anyways, because of my past, so I wasn’t surprised that they [Geo Group] didn’t do anything- that it was more about money [to them],” he added.

But Dewayne found support in other residents. They created their own support networks. “I was lost but the people that were there before me, the other residents, they were the ones posting resources on the board. Not the case managers. They’d share resources like ‘go here to get a job, go here to get clothing.’ The ones who needed help were the ones who helped each other.”

The revealing experience about the power of community stuck with Dewayne. It helped him find his calling — actively supporting his community by helping folks who are walking similar paths to his. He knew that with effort and dedication, he could help others improve their lives and support them in the way he once needed support.

“I come from being incarcerated,” Dewayne explained, “and some of our staff are former drug users, and so on. We have all types of people [at Hospitality House]. And if each one of us reaches out to someone, especially people who walk the same path that we just came down, then it’s up to us to help out.”

Because Hospitality House uses a peer-based model, many of our staff members look to their lived experiences as invaluable in helping community members overcome their own struggles. Dewayne continues to nurture that growth within his staff so they too can guide those seeking help as well as advance professionally within the social services field.

“It’s never too late to change, and it’s never too late to learn,” Dewayne emphasized. “So I bring that to my staff and then pass it on to the community. Everyone should think like that. Because the [criminal justice] system is not geared to help you. If we don’t do it, who else is going to do it?”

This past year, Dewayne and several Hospitality House staff members composed mostly of former lifers and seasoned activists launched a new program to support reentry folks— a combination of resources and services paired with a peer support group. “House Talk,” as Dewayne describes, “celebrates where you’re at, and pushes you to strive for more.”

People formerly incarcerated, especially those with double-digit or life sentences need guidance. Society is not set up to help formerly incarcerated folks successfully reintegrate into the community. Dewayne breaks it down, “You think of prison reform, but what about daily living? Providing for your family, providing for yourself? One strike against you, two strikes against you, and if you’re formerly incarcerated and a person of color and that’s like four strikes against you”.

Dewayne is happy with the direction our organization has been heading. “Hospitality House has grown a lot in these last ten years,” he says. “Grown in different ways.”

“We’re getting more political, looking at the why of things, and asking ‘why are you still doing the homeless like this’ and then helping [community members] find their voice. You can come to the Community Building Program , get connected to the Community Organizing Work Group, teach people to go to City Hall and speak up, to have their voice in the mix. Getting people out to vote. A lot of poor and low income folks don’t usually vote, but we’re getting them out to vote. I like where Hospitality House is going.” Dewayne acknowledged.

Of course, we have a long road ahead in the fight for social justice, but community leaders like Dewayne Cobb make that road feel a lot less rocky. Hospitality House is privileged and proud to have Dewayne as a part of our Leadership Team. Here’s to another ten years!

Dewayne began his journey at Hospitality House as both an on-call peer staff and on-call custodian, but it wasn’t long before he transitioned to a full-time position. Dewayne’s colleagues and supervisors quickly saw that he had a knack for connecting with his co-workers and community members alike. Dewayne possesses innate leadership qualities — a shoulder to lean on, an ear to bend, a great sense of humor to lift your spirit, and most importantly, a grounded presence to make you feel sane when the world seems like it’s getting ready to swallow you whole. There are not a lot of people that can do that. For Dewayne it came naturally. And still does.

Over the past ten years, Dewayne has worked his way up through several positions at Hospitality House, giving him useful insight on agency needs and issues. Dewayne’s extensive knowledge of the services Hospitality House offers, coupled with his engaging personality, make him an exceptional Program Manager at one of Hospitality House’s flagship programs, the Tenderloin Self-Help Center. Beyond that effective combination, Dewayne has a unique perspective on what genuine community support should look like.

Dewayne’s path to Hospitality House was a challenging one. After his release from prison, he resided at 111 Taylor, a so-called “community reentry center” located just blocks away from Hospitality House. This particular halfway house is owned by Geo Group, one of the largest private prison companies in the world. Geo Group operates “126 secure facilities, processing centers, and community reentry centers encompassing approximately 94,000 beds” in the United States. Put another way, that’s 126 prisons, immigration detention facilities, and halfway houses - profit-making off the misery of others.

Ironically, 111 Taylor is the site of the historic 1966 Compton Cafeteria Uprising, a collective queer resistence to police harassment and the first known LGBTQ related uprising in the United States (preceding the well known 1969 Stonewall Uprising in NYC). The founding of Hospitality House can be attributed to this uprising but we’ll save that story for another time.

Dewayne describes 111 Taylor as simply a bed to sleep in and nothing more. There was no support, no guidance, no direction.

“[111 Taylor] never connected me to jobs or resources. I had been incarcerated for a while, I needed clothing. I had never lived in the Bay Area. They sent me to job search, but I had nowhere to go, I couldn’t even get a bus token. They said ‘figure it out and bring us proof you’ve been job searching.’ I was lost here,” he admitted. “I don’t expect that much from most people anyways, because of my past, so I wasn’t surprised that they [Geo Group] didn’t do anything- that it was more about money [to them],” he added.

But Dewayne found support in other residents. They created their own support networks. “I was lost but the people that were there before me, the other residents, they were the ones posting resources on the board. Not the case managers. They’d share resources like ‘go here to get a job, go here to get clothing.’ The ones who needed help were the ones who helped each other.”

The revealing experience about the power of community stuck with Dewayne. It helped him find his calling — actively supporting his community by helping folks who are walking similar paths to his. He knew that with effort and dedication, he could help others improve their lives and support them in the way he once needed support.

“I come from being incarcerated,” Dewayne explained, “and some of our staff are former drug users, and so on. We have all types of people [at Hospitality House]. And if each one of us reaches out to someone, especially people who walk the same path that we just came down, then it’s up to us to help out.”

Because Hospitality House uses a peer-based model, many of our staff members look to their lived experiences as invaluable in helping community members overcome their own struggles. Dewayne continues to nurture that growth within his staff so they too can guide those seeking help as well as advance professionally within the social services field.

“It’s never too late to change, and it’s never too late to learn,” Dewayne emphasized. “So I bring that to my staff and then pass it on to the community. Everyone should think like that. Because the [criminal justice] system is not geared to help you. If we don’t do it, who else is going to do it?”

This past year, Dewayne and several Hospitality House staff members composed mostly of former lifers and seasoned activists launched a new program to support reentry folks— a combination of resources and services paired with a peer support group. “House Talk,” as Dewayne describes, “celebrates where you’re at, and pushes you to strive for more.”

People formerly incarcerated, especially those with double-digit or life sentences need guidance. Society is not set up to help formerly incarcerated folks successfully reintegrate into the community. Dewayne breaks it down, “You think of prison reform, but what about daily living? Providing for your family, providing for yourself? One strike against you, two strikes against you, and if you’re formerly incarcerated and a person of color and that’s like four strikes against you”.

Dewayne is happy with the direction our organization has been heading. “Hospitality House has grown a lot in these last ten years,” he says. “Grown in different ways.”

“We’re getting more political, looking at the why of things, and asking ‘why are you still doing the homeless like this’ and then helping [community members] find their voice. You can come to the Community Building Program , get connected to the Community Organizing Work Group, teach people to go to City Hall and speak up, to have their voice in the mix. Getting people out to vote. A lot of poor and low income folks don’t usually vote, but we’re getting them out to vote. I like where Hospitality House is going.” Dewayne acknowledged.

Of course, we have a long road ahead in the fight for social justice, but community leaders like Dewayne Cobb make that road feel a lot less rocky. Hospitality House is privileged and proud to have Dewayne as a part of our Leadership Team. Here’s to another ten years!

Two Cities - A Tale...

An essay by Hospitality House Executive Director Joe Wilson

Two Cities - A Tale…

The pain and trauma that nonprofit workers are carrying every day is palpable, and deep. Seeing the communities in which they work, that so many grew up in, under siege, under assault by the ravages of a deadly disease – while seemingly abandoned to fend for themselves. In the City of St. Francis.

Communities of color, our communities, being crushed by the sheer weight of it: a perfect storm of poverty, racism, and disease. Where even having a tent to protect one's self – and others, as it turns out, according the CDC - is considered an affront to our delicate sensibilities. Not the crime of poverty, mind you, just poor people.

Nonprofit workers, first responders, health professionals, those who care for others, and those who stock our grocery shelves - are living that trauma every day, then taking it home. Hoping against hope they aren't bringing more harm to others: their own families.

The pain is more than dollars and cents, or abstract accounting entries. It is real people, real lives, real harm. It is emotional violence - killing our souls, cutting out the heart of our humanity. We are crying and dying inside.

We remind ourselves every day why we came to this work to begin with: to help heal the wounds of oppression, not to cause more harm. To somehow make something - any single thing, just a little bit better. And yet. The harm that is seen all around us - and felt, internalized deep inside - in the eyes of people on the street. Wondering if anyone will ever come to their rescue, our rescue - if anyone cares if they live or die. If they matter at all. If any of us matter.

In fact, the communities in which we work, of which we are part, and claim to represent - bound together by MLK's garment of destiny - these communities have never been prioritized. Not women fleeing domestic violence. Not people of color. Not immigrants. Not seniors, not disabled people. Not the LGBTQ community. Not poor people. Not homeless people. Not surprising then, that those who stand shoulder to shoulder in this fight against time and against mortality, are not valued highly. In the City of St. Francis.

This pandemic has attacked the core of community connectedness, imposing separation on a community already isolated - and all that we have lived for and fought for is unraveling all around us. Every day. Every hour. Every minute.

No one has to explain to us how difficult it is, how challenging it is, and oh-my-goodness-the-hard-choices-we-have-to-make! Excuse me, that’s what people of color, working people, poor people do every hour of every damn day, make impossible choices in order to live.

What we need to know is: do our leaders have the stuff that poor people are made of?

We know deep in the essence of all that we are, all that keeps us human, we will not go gently into that good night. The struggle chose us, and we choose to fight. We are throwing down, for our community, here, in this moment, for all of us. For all that we can be.

In the words of John Lewis, good trouble is coming your way…in the City of St. Francis.

Charles Blackwell: Art Can Empower

Story by Tess Davis. Photo by Anastasiia Sapon

|

In the Matter of Black Lives

The blood has been spilled, innocent blood Black bodies bluesed blood From long, long ago Ancestors blood which rises to give off a stench Crying, just just justice And how just is this mud The hands which shed this blood where a mask Their hands tremble and shake To cover their shame Only to exposure their guilt And a nightmare of who they are And what they have become The stench continues to rise Everytime the ancestors children are murdered This blood rumbles and rises See this blood mixing with mud Swirling upstream Flowing downstream Then exploding |

Meet Mr. Charles Blackwell, a well known San Francisco/Oakland based artist and long time friend of Hospitality House. If you haven’t met Mr. Blackwell, it’s likely you’ve seen some of his eye catching artwork at one of Hospitality House’s annual art auctions. Or perhaps you’ve seen his artwork displayed on Market Street, behind 8-foot tall glass windows, visible for all of the bustling Mid-Market and 6th Street corridor to enjoy. And if that still doesn’t ring a bell, well then I invite you to continue reading. Mr. Blackwell is best known for his use of bright colors and bold lines to create striking works that speak to elements of his own lived experience-- his love for jazz, his passion for justice, and his unique personal struggles. Charles also uses the art of spoken word to express himself. He lives by the phrase, “take your challenges and make them an asset”. As a young man, an unexpected accident left him without the majority of his eyesight, leaving him with only limited peripheral vision. Fortunately, he has found that the loss of his vision has opened him up to a new way of working, a newfound freedom within his artistic practice. The loss of eyesight is not the only struggle he’s grappled with throughout his lifetime. Charles is a black man living in America, a country that is, as he puts it (with a nod to the late Martin Luther King Jr.), sick to the core. A nation that continues to cover up it’s horrific past, rather than acknowledge it. However, the act of recognizing the county’s sickness is “probably the only thing that allows me to have some sanity,” he explains. His advocacy work began at a very young age and continued into college where he fought to establish Black Studies on campus. His fight for justice didn’t end there. Much of Charles's artwork speaks to the atrocious violence and abuse African American’s have endured through their history in the United States. He is a firm believer in confronting this painful past and the subsequent years of oppression by bringing it to the foreground for discussing, educating, dismantling, growing, progressing, and eventually changing people’s attitudes. Charles commends the Black Lives Matter movement for being agents of change. "I admire [the BLM Movement] 'cause it's forcing these issues to the surface. And racism that is so deeply embedded in this country." He continues, "They're changing policy and pushing for real change." Charles confronts racism, violence, and black oppression through his paintings and poetry with an intent to encourage dialogue. He recalls an encounter he had while preparing a piece for a show. “I did a piece for an exhibit in Richmond, it’s called: The Art of Living Black... [my piece] was red, dark red, and it was the lynching of two people... it was a strong piece that really provokes anger. And someone came by to complain about the piece being ‘so terrible’ and asked to have it taken down. So I asked her, ‘Do you know about our history?’ But that’s the idea. You present it to confront and create that conversation. Otherwise, how is change going to come about? You have to create the conversation or else you go home and bury it then blow up later on.” While Charles recognizes that these are tough conversations to have. He explains in detail how white racism (“The act of racism perpetuated by white people and upheld through white supremacy.” as Charles puts it) will get inside your mind and destroy your spirit. It will eat away at you. You cannot leave it there to sit unchecked the way a white supremecist society expects you to. “America says, ‘Okay, just obey the rules, you’re fine. We have policy in place, we’re not racist,’... and then it explodes. It’s like Langstone Hughes’, What Happens to a Dream Deferred, does it shrivel up? Does it explode?”, he expounds. Charles' work goes far beyond confronting racism. Much of his art -- both literary and visual-- includes elements intended to not only speak to the experience of other African American artists, but to lift their minds and spirits. This is absolutely crucial, because as Charles explains, there is so much damage that is done to the self esteem of a black child through racism. During those formative years of development, while a child is discovering their identity and relation to the rest of the world, they see, hear, feel, observe racism all around them, constantly being told, as Charles explains, “You’re no good,” or “You’re not good enough to be here.” Charles also feels that he can use his artwork as a tool to uplift to the African American community. Through his work with the National Conference of Artists (it was oldest operating African American arts organization in the United States), he was inspired by styles and techniques he found in African art. The movement, the lines, the shapes-- they spoke to him in a way he had never felt before, so he began to incorporate them into his own creative work. “I drew from that to create pieces that reached the spirit, the core self-esteem of African American artists,” he said, “There is beauty in these art pieces, beauty that we can see within ourselves.” Art allows us to connect in ways we may have never thought possible, ways that can surprise us, touch us so deeply. We’re brought closer together-- even by someone we’ve never met. Charles recounts a moment he had at Hospitality House where he connected with a complete stranger, a man visiting from DC who was incredibly moved by Charles’s work. He was so inspired, it was almost as if the work was made for him. “I’m inspired by anyone that tells me they're inspired by my work. It’s a beautiful compliment. But this man was African American. To reach him lets me know that what I’m doing resonates. That we can rise up out of that deep, dark place that society puts us.” he said. Charles knows the power of art. He has experienced the transformative beauty of finding something that resonates deeply, employing it in his own practice and passing it forward. He understands what art it is capable of-- what it can do for himself, for his community, for the larger movement. Charles reminds us, “Art can empower.” |

Sylvester "Slick" Guard: An Artist From & For The Community

Story by Tess Davis

“When it comes to my art, it’s just something I've alway done. I don't really have any control of it, it just comes out, it is what it is.”

Meet Sylvester “Slick” Guard, long time friend of Hospitality House, local artist, and self-identified “dude that knows how to use a pen.” If you’ve seen his work, you know that’s an awfully humble title. Slick is well known in San Francisco, especially in the Tenderloin and South of Market Area, for his bright, colorful, and beautifully crafted murals. But Slick’s not just another talented artist living in San Francisco (because let’s be real, the Bay Area is overflowing with talent), Slick is also known for being from and for the community.

Born and raised in the Bay Area, Slick began his journey making art when he was just old enough to pick up a pen. By the age of five, he had won his first art award from the Oakland Unified School District. Four years later, young Slick was painting his first mural. Fast forward to now, and he estimates he’s done about 30 murals, the majority of them in San Francisco.

Slick’s love for art goes far beyond simply creating it. He believes in sharing his art with his community, to inspire those who came before him and those who will come after. He paints messages that empower TL and SOMA residents, depict their community in a way they can feel proud of, and give them a sense of ownership. An example of this is one of most recent murals in Stevenson Alley (SOMA). “It’s indicative of the people in that building and the people who sit in that alley. And they wash it everyday, they take care of it, cause they know I'm from town...they respect it," he explains.

Beyond inspiring his community, Slick is actively seeking new opportunities to bring more neighborhood artists into the mix. “I want to see a wall and then raise the funds for it..I want to get these projects and keep them in the neighborhood. If you live in the Tenderloin, you get the first crack at the wall. We have too many rich guys painting our walls and they’re not painting messages that are good for us...clowns, three eyed pigeons, wine bottles, needles. We have enough of that already. If you want to be edgy, paint a forest...Paint some positive images of the people you see around you.”

Slick wants a Tenderloin where the people who live in the community are the ones doing the murals, painting artwork with hopeful messages that they get to wake up to everyday. Just like the larger Bay Area, the Tenderloin does not fall short of talent and Slick knows this. “You see all those people standing out front [on Market Street], those are artisans, those are poets, those are writers...We owe them the chance to have their voices heard.”

Slick won’t stop pushing until he sees his community not just represented but thriving in the San Francisco art scene, where Tenderloin and SOMA artists are painting their neighborhood murals, displayed at local exhibitions, and represented by SF galleries.

“It’s time we showcase what our city can do and what makes our city so great.”

Check out Slick’s work on Instagram, @slickpoppy.

Meet Sylvester “Slick” Guard, long time friend of Hospitality House, local artist, and self-identified “dude that knows how to use a pen.” If you’ve seen his work, you know that’s an awfully humble title. Slick is well known in San Francisco, especially in the Tenderloin and South of Market Area, for his bright, colorful, and beautifully crafted murals. But Slick’s not just another talented artist living in San Francisco (because let’s be real, the Bay Area is overflowing with talent), Slick is also known for being from and for the community.

Born and raised in the Bay Area, Slick began his journey making art when he was just old enough to pick up a pen. By the age of five, he had won his first art award from the Oakland Unified School District. Four years later, young Slick was painting his first mural. Fast forward to now, and he estimates he’s done about 30 murals, the majority of them in San Francisco.

Slick’s love for art goes far beyond simply creating it. He believes in sharing his art with his community, to inspire those who came before him and those who will come after. He paints messages that empower TL and SOMA residents, depict their community in a way they can feel proud of, and give them a sense of ownership. An example of this is one of most recent murals in Stevenson Alley (SOMA). “It’s indicative of the people in that building and the people who sit in that alley. And they wash it everyday, they take care of it, cause they know I'm from town...they respect it," he explains.

Beyond inspiring his community, Slick is actively seeking new opportunities to bring more neighborhood artists into the mix. “I want to see a wall and then raise the funds for it..I want to get these projects and keep them in the neighborhood. If you live in the Tenderloin, you get the first crack at the wall. We have too many rich guys painting our walls and they’re not painting messages that are good for us...clowns, three eyed pigeons, wine bottles, needles. We have enough of that already. If you want to be edgy, paint a forest...Paint some positive images of the people you see around you.”

Slick wants a Tenderloin where the people who live in the community are the ones doing the murals, painting artwork with hopeful messages that they get to wake up to everyday. Just like the larger Bay Area, the Tenderloin does not fall short of talent and Slick knows this. “You see all those people standing out front [on Market Street], those are artisans, those are poets, those are writers...We owe them the chance to have their voices heard.”

Slick won’t stop pushing until he sees his community not just represented but thriving in the San Francisco art scene, where Tenderloin and SOMA artists are painting their neighborhood murals, displayed at local exhibitions, and represented by SF galleries.

“It’s time we showcase what our city can do and what makes our city so great.”

Check out Slick’s work on Instagram, @slickpoppy.

#BTLM Pride Celebration

Story by Tess Davis

|

|

On Friday, June 26th, Hospitality House’s Community Arts Program (CAP) hosted their yearly Pride Celebration. However, this year looked a little different..

Due to Covid-19, the CAP staff and neighborhood artists had to take extra measures to protect themselves and one another-- masks, loads of hand sanitizers and a safe six feet distance at all times. They even passed out personal protective equipment to anythine who needed it. But that didn’t stop them from having a good time. “It was really great to find a safe way to connect with the community. We are all missing our broader communities and I think it was a balm for all of us at the art program to be together, even socially distanced, in some way during this time.” There was pizza, music, dancing, colorful chalk art etched along Market Street, drawing passerbyers over from all directions. Staff passed out personal protective equipment (masks, gloves, etc.) and the highlight: screen printed patches and t-shirts and homemade buttons with what may be the most important message of our time, Black Trans Lives Matter. |